What do tumor cells, the placenta and malaria all have in common? A sugar, apparently, but not just any old sugar: one that might pave way for the development of broad treatment effective against a range of cancers.

This discovery, published in Cancer Cell, is the result of a collaboration between the University of British Columbia, the University of Copenhagen and the BC Cancer Agency, and finally offers an explanation for a curious observation that scientists long struggled to explain. Pregnant women, it turns out, are particularly susceptible to malaria. And it was the search for an explanation that ultimately led to this important find.

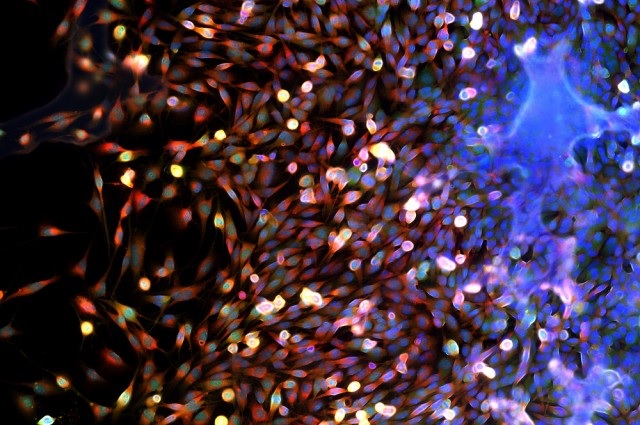

The researchers discovered that the malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, engineers infected red blood cells to produce and present a malarial protein called VAR2CSA, which sticks to a type of sugar exclusively found in the placenta. Or so they thought. Tumor cells, it was revealed, also express a virtually identical sugar molecule. Both molecules are a type of chondroitin sulfate. That wasn’t a tremendous shock, though, because these two distinct tissues do share similarities: they both grow very rapidly and in an invasive manner.

“Scientists have spent decades trying to find biochemical similarities between placenta tissue and cancer, but we just didn’t have the technology to find it,” study coauthor and project leader Mads Daugaard said in a statement. “When my colleagues discovered how malaria uses VAR2CSA to embed itself in the placenta, we immediately saw its potential to deliver cancer drugs in a precise, controlled way to tumors.”

To examine this idea, the researchers generated VAR2CSA in the lab and attached one of two toxic molecules to it before testing out the novel compound on a bounty of both normal and tumor cell lines representing various different cancers. Encouragingly, the drug displayed specificity for the cancer cells only, attaching to them and delivering a deadly toxic blow after being absorbed. In fact, the compound was so potent that it successfully targeted and killed 95% of the cancer cell lines investigated, which included brain, blood, prostate and breast.

But sticking your finger in a tissue culture dish will quite easily kill cells, so the researchers took their drug one step further and tested it out on mice that were implanted with three different human cancers, all of which responded. In those with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, the tumors shrunk to around a quarter of the size of those in the untreated group, and two out of six treated mice with prostate cancer went into remission just one month after receiving the drug. Last but not least, five out of six mice with metastatic (tumors that have spread) breast cancer were cured.

“There is some irony that a disease as destructive as malaria might be exploited to treat another dreaded disease,” lead author Ali Salanti said in a statement.

Of course, we can’t get overexcited about animal trials, but the results are nonetheless encouraging. And two companies are already working towards developing a compound suitable for trials in humans, but that will take at least three to four years.

Source link : http://www.iflscience.com/health-and-medicine/malaria-protein-could-give-us-broad-cancer-treatment